Another energy project has been scuttled that could have provided some relief to New Hampshire and New England households and businesses who are paying among the highest prices for energy of any state in the nation. I believe the project would also have contributed to the important goal of reducing carbon emissions in NH and New England (more about my support for reducing carbon emissions and some controversial policies to accomplish that in a future post). No doubt any proposed energy project is better when forged and tempered through a process of public review and debate. But the withdrawal of proposed wind energy projects, and more recently the Northeast Energy Direct (NED) natural gas pipeline project, as well as the difficulties encountered by some solar projects in the state, question how committed many residents and some policymakers in NH are to finding solutions to an energy climate that is widely recognized as detrimental to households, businesses, and the NH economy. As opponents of pipeline, wind, and solar projects claim another “victory” in NH, an admonition given to Pyrrhus, a Greek general and ruler of Epirus comes to mind. After a costly victory over his Roman enemies by Pyrrhus, the Greek philosopher Plutarch reportedly told Pyrrhus that another, similar “victory” would ruin him. If the “ruin” that could occur only affected the combatants in NH’s energy infrastructure battles, instead of the 1.4 million non-combatant “energy civilians” in the state, Plutarch’s warning might be useful. But there are no “generals” and no real leaders or statesmen and stateswomen battling NH’s energy constraints and so the casualties of our state’s inability to take control and direct its energy future will be most broadly spread across the state’s population.

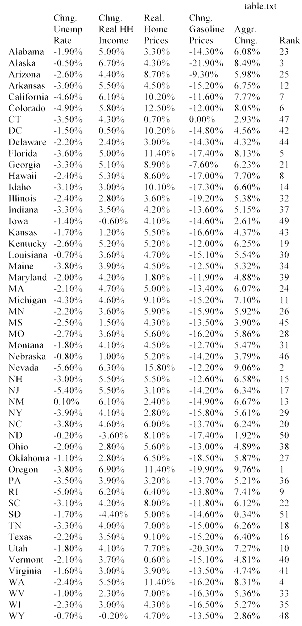

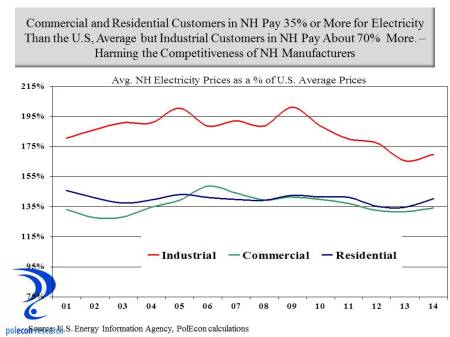

This post highlights some of my calculations of the costs to NH of the defeat (or victory as opponents would argue) over the Northeast Energy Direct natural gas pipeline proposal. To begin, let’s reiterate the cost disadvantages faced by consumers of electricity in NH. The chart below shows that through 2014, residential and commercial electricity customers paid, on average, about 35 percent higher rates than the national average, while industrial customers paid a whopping 70 percent higher rates than the national average.

The NED Project’s Impact on Natural Gas and Electricity Prices

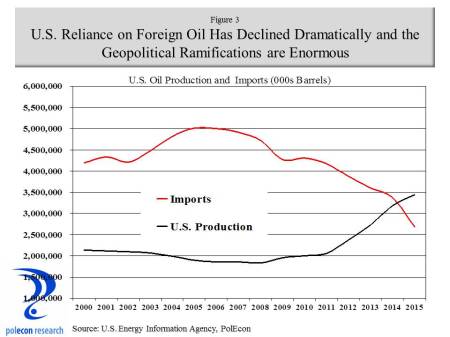

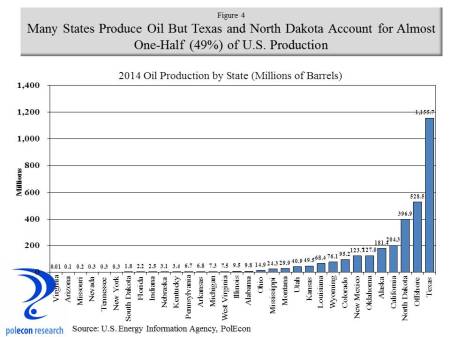

Natural gas prices have been lower in recent years as a result of increased U.S. production, largely from the Marcellus and Utica shale formations in Ohio and Pennsylvania. But as I noted in this post, a lack of pipeline capacity precludes NH and New England from realizing the full benefits from declining natural gas prices. The increased supply of natural gas from nearby sources enabled by the Northeast Energy Direct project would impact natural gas prices in NH and New England. Price reductions would result in direct savings to residential, commercial, and industrial consumers of natural gas and would also result in electricity prices that are lower in NH than without the Northeast Energy Direct project. New England’s wholesale power prices are closely related to natural gas prices because of the region’s dependence on gas-fired power generation capacity. By reducing spot prices for natural gas in New England, the NED Project will have a direct impact on New England’s wholesale power prices.

At least eight separate studies have forecast lower natural gas prices in New England resulting from an increase in pipeline capacity into the region. Even one study from the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office, while suggesting an increase in pipeline capacity to New England isn’t needed to assure reliability of electricity supplies in the region (inaccurately I believe and contrary to reports by others, including the operator of the New England Energy grid), recognizes that increased pipeline capacity would result in lower regional natural gas prices.

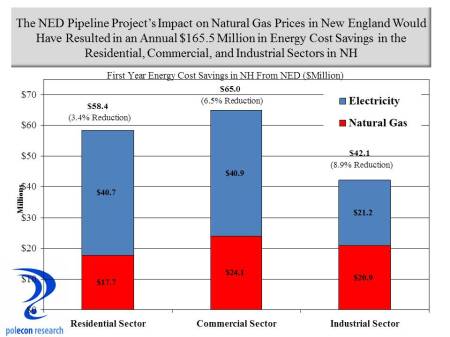

There is a range of estimates of the price impacts from an increase in natural gas supply to the region. My estimates of energy cost savings in NH use one of the more conservative estimates of the price impacts of increased supplies to the region as documented in a study by ICF International. I used historical data on both natural gas and electricity consumption by sector (residential, commercial, industrial) in NH from the U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA) as well as forecasts of future consumption based on the EIA’s regional forecast for growth in natural gas and electricity consumption and applied ICF natural gas and electricity price reduction estimates to consumption forecasts in NH to estimate savings to customers in the state that would result from the operation of the NED pipeline. In the initial full-year of pipeline operation I estimated the savings to natural gas and electricity consumers in NH to be $165.5 million. The breakdown of saving by source and sector is presented below. Savings represent about 3.4 % of the 2014 energy expenditures of NH residential consumers, 6.5% of commercial sector energy expenditures, and 8.9% of the energy expenditures of industrial consumers.

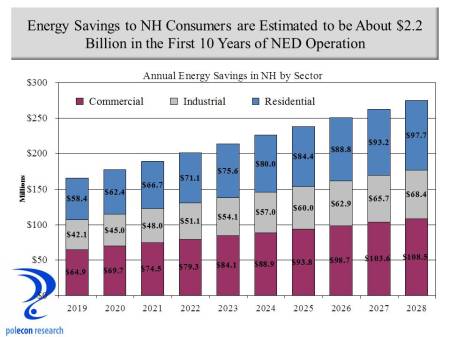

Using the same sources and methods, I estimate the 10 year energy cost savings to NH natural gas and electricity consumers would be just under $2.2 billion in nominal dollars as a result of the Northeast Energy Direct project.

Additional Benefits of Increased Regional Access to Natural Gas

There are other potential benefits from NED that have been less talked about. Much of NH has limited or no access to pipeline natural gas from local distribution companies. The lack of access to natural gas increases energy costs for households and businesses in many regions the state. In particular, lack of access increases the economic disadvantages currently faced by most rural regions in the state. Natural gas is most available in the populated regions of Southern NH closest to regional pipelines and the lateral pipelines operated by local utilities who purchase natural gas from the regional pipeline operators. The proposed NED pipeline would have passed through a portion of the state where the economy has lagged for some time and regions that could most benefit from access to pipeline natural gas. The NED would increase capacity but local utilities would have to add lateral pipelines to serve communities, households and business in places like Keene, Claremont, Cheshire, Sullivan and Grafton Counties.

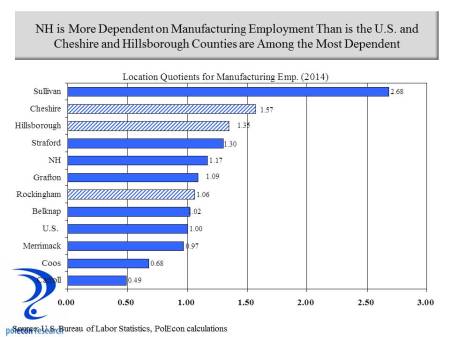

Along with extremely high electricity prices for industrial consumers relative to the U.S. average, the lack of access to natural gas is a significant disincentive to operating a manufacturing facility in much of New Hampshire, as nationally, natural gas accounts for 40 percent of the purchased energy of manufacturers on a BTU basis. There is anecdotal evidence that manufacturers nationally are starting to react to lower natural gas prices by planning to open new facilities in the United States. There are other influential factors, including rising employment costs overseas, but those industries for which natural gas is an important input are anticipating an advantage of locating their operations in the U.S.. Cheshire and Sullivan Counties are among the most manufacturing dependent regions in the state and access to utility natural gas would especially benefit communities in those regions. The chart below presents location quotients which represent the concentration of manufacturing employment in each NH county relative to the concentration of manufacturing employment in the U.S. overall. A location quotient of 1.00 indicates a region where the concentration of manufacturing employment is identical to the concentration of manufacturing in the the U.S. economy overall. Location quotients above about 1.20 suggest counties where manufacturing is especially important to the regional economy. Shaded bars represent counties through which the NED project would pass. The NED would not pass through Sullivan County but its proximity would make lateral access to gas from the pipeline feasible.

Increased natural gas supplies and lower prices will be especially helpful to smaller manufacturing firms which face higher prices in New England but also face larger natural gas price differentials relative to larger manufacturers than anywhere in the country. High prices and larger price differentials create a strong disincentive for new and emerging manufacturing firms to operate in New Hampshire and may be contributing to an “aging” in the manufacturing sector in the state.

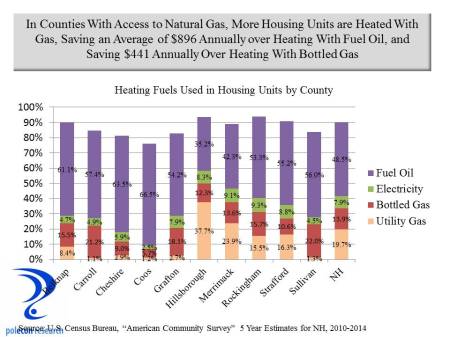

Access to natural gas would also benefit households. Just under 20 percent of households in New Hampshire use pipeline natural gas for heating and another 13 percent use bottled gas but there are large regional variations in the availability of natural gas for heating. Again, regions of the state that are considered economically disadvantaged, in most cases, have the least access to pipeline natural gas. Access to pipeline gas won’t guarantee a reduction in disparities in the economic performance of various regions of NH but it would help households and manufacturers in regions where the economic performance has lagged.

The savings for households heating with pipeline natural gas is substantial. The table below shows the average cost differential in annual heating costs between housing units heated with pipeline natural gas and other sources. The difference between pipeline natural gas heating and fuel oil – the largest source of home heating fuel in NH – averaged over $890 annually between 2010 and 2014. By lowering natural gas prices the differential between homes heated with natural gas and other sources (other than solar) are likely to widen. The NED would increase opportunities for more communities, regions and more homes to be heated with natural gas in New Hampshire, amplifying the potential savings estimated here for NH households and the NH economy associated with lower natural gas prices.

Factoring the impacts of the NED project on natural gas prices and disposable income for residential consumers (and not including the impacts on commercial and industrial consumers) I estimate that an additional 5,300 jobs would have been created in the first 10 years in response to the energy cost savings to households from the NED project. When the impacts on industrial and commercial consumers are considered the potential benefits of the project become even clearer.

Disclosure

I originally prepared more detailed estimates (than in this post) in a report I did for the proposed NED project. I write this blog (when I have time) because I enjoy researching and writing about topics that interest me, not to advance client interests. I think the report contained some good analyses and now that the NED proposal has been withdrawn and the company is no longer a client, I don’t feel conflicted writing about it here. The success or failure of the NED project had no impact on the compensation I received. The report addresses energy issues in NH that I have been writing about since long before my work for the NED project. It examines the usual economic impacts from the construction phase of the project but more importantly potential longer-term impacts of the project. The report also examines controversial topics such as potential impacts on tourism activities as well as fiscal impacts of the project. The report can be viewed here. Because the report was paid for by the NED project owners, critics will dismiss some or all of the findings. But a report that is paid for only means that its author(s) has some “skin in the game.” In a small state, and especially in NH, anyone who produces work that distorts findings or misleads policymakers won’t be offering services of value and won’t be working in the state for long. On the other hand, anyone without “skin in the game” or some compensated interest is pretty much free to make any claim without evidence, present any data, or any “analysis” regardless of its accuracy, without concern for the impact that it has on their business or professional reputation. I am not arguing that any information brought to policy debates that isn’t paid for has no value or is necessarily inaccurate or misleading, just that information that is not paid for by some interests is not is inherently or by definition more accurate or relevant than work that is paid for – there should be no “halo effect” for information entered into important policy debates simply on the basis of whether or not compensation was involved – compensated or not, information entered into the debate is provided by a party with a particular interest in the issue. The quality and accuracy of the analysis should determine its merits. I like to think that the ultimate test of the quality of an analysis is whether those who produced it will be around and willing to answer for its accuracy or inaccuracy when the time comes when that can be determined. I don’t think my analyses (or forecasts) are wrong that often but when they are I am available to answer to policymakers and others for it. I don’t think I would have had to answer for my my analysis of the impacts of the NED.