Small businesses fared the worst during the recent recession and hiring by small businesses has been slower to recover after this recession than it was following past recessions. Robust economic growth does not occur unless small businesses are confident, healthy, and hiring. With a fragile national recovery from recession that has not quickly helped to repair the balance sheets of most small businesses, and with a number of important public policies (regulatory, tax, health care etc.) still uncertain, it is not surprising that small businesses have been less than sanguine about the prospects for the economy and reluctant to hire. That may be changing, however, as the NFIB’s national index of small business optimism has begun to increase. The NFIB index is a pretty good predictor of the direction of job growth in NH and its latest up-tick is consistent with last month’s increase in payroll employment in New Hampshire.

Archive for the ‘NH Economy’ category

Small Business Optimism Improves

November 28, 2012Job Growth May Depend on Narrowing the “Skills Gap”

November 21, 2012A quick review: The “skills gap” explanation for slower employment growth this recovery posits that there are large numbers of jobs waiting to be filled but hiring is sub-par after the recession because of a lack of qualified candidates to fill those positions. Twice I have presented some evidence on the issue, here and here. Most of the concern and evidence about the existence of a skills gap addresses very high-skill technical, scientific, computer, and engineering occupations because our nation, and by extension our state, seem to perpetually be unable to produce enough individuals in those fields to satisfy industry demand. As a result we “import” a lot of that talent from foreign countries (more about this – I promise – in a future post). There is some evidence of this in NH. As the chart below shows, professional, scientific, and technology occupations are the largest, broad category of help wanted ads in the state. But they have also evidenced the smallest increase (a decrease actually) since the recession. There is still a significant demand but it may be that an inability to find qualified applicants has companies in need of those occupations from considering more hiring in the Granite State. A quick review of data for Massachusetts shows that demand for professional, scientific and technical occupations has increased during the same time period.

But more direct evidence of a skills gap comes from the demand for construction and production workers. I am especially interested in the potential skills gap for production workers. The chart above shows that demand for construction, production, and transportation workers has increased significantly since the recession. Although still a much smaller category of help-wanted ads than professional and technical jobs, the increased demand is consistent with anecdotal evidence I heard this week at a roundtable discussion of the Seacoast economy. At that discussion, representatives from industry, higher education, and economic development organizations cited specific examples of companies frustrated at their ability to hire skilled production workers. Some are forming partnerships with NH’s community college system to increase the supply of needed occupations. Those initiatives show promise and I hope the state’s four-year colleges and universities develop more partnerships to address the skills gap in professional, scientific and technical occupations as well because, increasingly, job growth in NH appears to depend on it.

Some Thankfull Job Growth Numbers

November 20, 2012The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its monthly report on state and local employment today and the good news is that, preliminarily, New Hampshire added 1,000 jobs in October. The bad news is that this is just 1,200 more jobs than the state had one year earlier in October of 2011. For optimists, the most recent trend is likely to be the most important and the monthly report is consistent with the rise in PolEcon’s NH Leading Index.

Nevertheless, the longer-term job growth trend in NH has been weak. Looking at growth in just private sector employment, the situation is no better for NH. As I have noted here, I believe job growth in NH is being underestimated but even if that is true, it is hard to see how the recent past will be revised enough to make NH’s job growth picture look comparable to that of our neighbor to the south or the U.S. as a whole.

The Skills Gap Part Deux: Some Evidence and Who’s Fault is it Anyway?

November 2, 2012A good national job growth report was released today that showed private sector job growth was up 184,000 in October. With government job losses at -13,000, total employment increased nationally by 171,000. We have to wait a few weeks to see NH’s job growth for the month but regardless of the number, the underlying causes of the state’s relatively slow recent job growth still need to be debated . A solid and empirically-based understanding of the factors influencing job growth rates is the only way to formulate effective economic policy in the state. I am on record as saying (probably too often) that I believe NH’s job growth numbers will be revised upward at some point (probably with the annual revisions released early next year). But even if that is true (errr, when it is conformed to be true), by historical standards, recent job growth in NH will still have underperformed. Whether job growth is slower now than in the past because employers are not willing to add additional workers or because they are not able to find qualified workers (the “skills gap” argument) is among the most important issues to understand in setting both national and state-level economic policies. If employers are unwilling to add employees that are readily available, then the efforts to spur job growth focus more on factors affecting businesses (tax rates, regulations, costs etc.). If job growth is constrained because employers are unable to find qualified workers to fill open positions, then the focus of efforts to spur job growth will be more effective if they look to increase the skills of the labor force, and/or better match them to the needs of employers. In reality this is not an either or question because inadequate attention to the needs of either employers or the workforce will produce sub-optimal economic growth. But in today’s polarized policy environment whatever light is shed on these issues is too often separated by an ideological prism that produces policy proposals aimed at either the needs of business or the needs of the workforce to the exclusion of the other. If job growth is slowed because there are too few qualified workers to meet the needs of businesses then it is not policy maker’s fault but they can help alleviate the problem by adopting more “human capital” policies. Businesses bear some of responsibility for any skills gap because studies have shown that businesses spend less time and money training workers than they did decades ago, and that more of the training that does occur is concentrated on management positions rather than mid- and lower- level positions. In an age when job turnover has accelerated, and the tenure of workers with one businesses continues to decline, it is understandable that businesses would be less willing to invest in workers who may only be with their firm for a short while. But who is more responsible for the decline in employer-employer loyalty and tenure? The labor market has been signaling strong demand increases in many occupations – especially technical and scientific occupations and increasingly skilled production occupations. Older and experienced workers may have difficulty responding to these demands if their experience, education or training is in occupations in less demand but why are younger and new entrants to the labor market not responding to these labor market signals by selecting the majors or training programs that would qualify them for more occupations in demand? One reason is that regardless of whether or not the labor market is signaling many job opportunities in technical and scientific occupations (or skilled production occupations), if large numbers of the emerging workforce don’t have the intellectual and academic rigor to study these subjects the positions will increasingly go unfilled, go elsewhere, or as I will document in a later post, be filled by foreign born workers.

Ok, that was a bit of a rant, now back to the core issue. Is there evidence of a skills gap in NH that is constraining job growth? The answer of course, as it is with almost all economic issues, is both yes and no and also something in-between and with a twist. I will share this evidence across several postings, today I offer one, small bit of evidence that suggests the skills gap is playing a larger role in disappointing job growth trends. I noted in an earlier post that help-wanted advertising has generally been on the rise in NH, while job growth has not. Some of this will be corrected with job growth revisions, but evidence that a skills gap is playing a role comes in the form of the percentage of help-wanted ads each month that are “new ads”. If help-wanted ads are rising and the number or percentage of new ads is rising similarly each month, that means positions are being filled at a fairly consistent rate, but if the number of ads is increasing, but the percentage of ads that are “new ads” is declining, that suggest that positions are not being filled or taking longer to fill – perhaps suggesting employers are having a harder time filling the positions or a skills gap. The chart below shows that indeed, the percentage of monthly help-wanted ads in NH that are :new ads” for the month has been slowly declining, providing some small bit of support for the skills gap explanation for job growth. A lot more evidence is needed, but given the importance of the issue in policy making, it is worth the effort to find or refute it.

What’s Behind NH’s Recent Net Out-Migration?

November 1, 2012I’ve written often about how important the ability to attract skilled, well-educated individuals is to NH’s past and future economic success. Appropriately, there is much concern over NH’s recent population losses resulting from movements of residents into and out-of the state and what it says about NH’s relative attractiveness. Not surprisingly, that concern results in many simplistic, inaccurate, and analytical flawed explanations for the patterns of migration to and from NH. I don’t have a book, video, seminar, or anything else to sell that depends of any particular explanation for NH’s migration patterns so I will let the data , as it becomes clearer, shape and evolve my theories on the phenomenon.

Here is the basic scenario: NH has traditionally been a magnet for residents moving from another state (most prominently from another Northeastern state – especially MA). During the past decade NH has attracted less net in-migration from other states, especially during the second half of the decade, culminating in net out-migration at the end of the decade. The resulting concern by many (including me) is that NH may be losing its fundamental attractiveness relative to other states. Because NH has relied on in-migration to fuel growth in “human capital” and the economy, this would imply very bad things about the future of our state. I worry a lot about NH’s attractiveness but my answer to the question of whether the state has lost its attractiveness is: “no…….not yet“. Lets look at migration to and from the state during the recession (chart below). During the recession the patterns of the past several decades were largely the same – albeit with different magnitudes. NH gained and lost a lot of residents from other Northeastern states, and smaller numbers from other states in the South and West.

The difference in recent years has been that the positive net flows to NH have been smaller for states that traditionally send NH a lot of residents (the Northeast), while the states with whom NH traditionally has net negative outflows have been larger (largely states in the south and west). But is this a sign that NH is now less attractive? I don’t think so (yet) and here is why. Since the housing and financial crisis and subsequent recession, the U.S. Census Bureau reports that state-to-state movement in the U.S. (on a % basis) has been about as low as it ever has been. One reason for that, many economists believe, is the fact that there were fewer places to move to that had stronger economic growth that often drives migration. But another important factor has been the phenomenon of “housing lock.”

Because of the housing market bust and subsequent housing equity, credit and financial issues, both the selling and buying of homes were disrupted or impossible for large numbers of homeowners in NH and across the country. That has especially profound impacts on net migration to NH. I can’t explain in detail here, but migration patterns in NH indicate that the state has been especially attractive to and a magnate for 30-44 yr. old, two wage-earner married couple families with children. To move to NH they typically have to sell a house in their native state and buy one in NH. Each of those was a lot more difficult at the end of the last decade. I believe this reduced our core demographic of potential in-migrants. At the same time, the housing market crash had less of an effect on the ability of the young, and non-homeowners to move from state-to-state. This is the demographic group that traditionally has shown net out-migration from NH. So the groups most likely to choose NH were most constrained from doing so during the last half of the 2000s, while the groups most likely to leave NH were not constrained from doing so by “housing lock” or other housing market issues. The result – much lower rates of net in-migration to the state. This explanation doesn’t account for all of the recent decline in net migration to NH, but it surely has played a significant role in the trend.

What Will the “Fiscal Cliff” Mean for NH?

October 30, 2012For an economy struggling to gain altitude it is hard to see how the impending spending cuts and tax increases associated with the “fiscal cliff” will do anything in the short-term but bring the economy to stall speed or push it back into recession. At a time when compromise is seen as weakness and ideological impurity, an agreement must be reached in order to avoid the negative effects of the the fiscal cliff. Depending on what is included, the ‘fiscal cliff includes anywhere from $500 to $700 billion in combined spending cuts and tax increases (many via the expiration of temporary cuts).

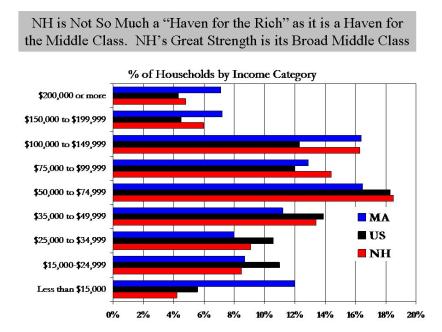

All states will feel the effects of the elimination of the temporary cut in the payroll tax but states with a higher percentage of high-income taxpayers will likely be affected more by the expiration of Bush era tax cuts. Despite often being characterized as a “tax haven” for the rich, NH is much more a “haven for the middle class” as it has a somewhat higher percentage of high-income households than the U.S. (but much lower than MA) and a relatively smaller percentage of lower- income individuals. The percentage of high-wealth individuals in NH is above the U.S. average, but the percentage of income taxes paid by those making $200,000 or more in NH is lower than 24 other states.

States where higher-wealth individuals pay a larger portion of the state’s tax burden are likely to be relatively more affected by the tax cut expiration provisions of the fiscal cliff. But NH will still see an estimated increase in payroll taxes of about $650 million, a significant drop in disposable income in the state. In addition, a study by George Mason University’s Center for Regional Analysis estimates that the defense department and non-defense department budget cuts that will result from the fiscal cliff will cost NH about 6,300 jobs and $325 million in labor income. NH no doubt will take some solace from the fact that Massachusetts is likely to see nearly 10 times the job losses from budget cuts to defense and other purposes (especially medical) and as a result of their high percentage of high-wealth households.

I want to think a reasonable resolution will be found that avoids the worst of the potential problems from the fiscal cliff. Fiscal tightening is clearly warranted, and it appears almost certain that at a minimum the payroll tax holiday will be allowed to expire as well as the Bush era tax cuts for upper income households. It is also almost certain that long term unemployment insurance benefits will be allowed to run out. After that, it all depends on one four-letter word – compromise.

The Disconnect Between the Cost of Generating Electricity and Retail Prices

October 24, 2012It is hard for consumers of electricity to understand why retail prices are what they are and how they are determined. It is beyond one blog entry to fully describe the process but in overview, the suppliers of electricity (generating companies) in a region offer to supply electricity to the market at a given price and the offers are accepted beginning with the lowest cost providers first, until enough energy is supplied to meet expected demand in the region. The price of electricity offered by the last electricity generator needed to meet the regional demand determines the market price paid by companies that supply the electricity to businesses and consumers. Retail prices are a function of the market price of electricity, plus many other costs such as transmission, special infrastructure charges, and profits by suppliers, among others. Much of these costs are determined at the state level by regulators, as well as the characteristics of the retail electricity market in the state (competition) and the practices and policies of the companies that supply electricity to retail markets.

The end result is that retail prices for electricity in any state bear only a limited relationship to the cost of generating electricity in the state. The chart bellow shows that the cost to generate 1 million BTUs of electricity in New Hampshire is about in the middle of all 50 states. Vermont is also relatively low. Both states have a relatively lower generating cost per million BTUs because a significant portion of the electricity produced in their state is from nuclear generators.

The correlation between the fuel costs to generate electricity in a state and retail prices per 1 million BTUs is modest, explaining less than one-third of the price per million BTU at the retail level. The chart below show that despite fuel costs that are in the middle of the pack, NH, VT and CT have high retail prices per million BTU of electricity. The regional nature of electricity markets along with the policies of state governments and the actions of individual retail sellers of electricity all play a role in disconnect between costs for generating electricity and prices at the retail level. We don’t have much control over the supplies of electricity beyond our state but we do have some control over the mix of suppliers of electricity which determine the cost of fuel for generation and we have a lot of control of the structure of retail markets and many other factors that determine the non-generating costs of electricity in the state and ultimately prices at the retail level.

The Changing Banking Market

October 23, 2012Public antipathy toward large financial institutions may have been building throughout much of the past decade but it surely peaked during and immediately following the recent recession and the financial crisis that helped precipitate it. One result appears to be a changing market structure for deposits and loans at financial institutions in NH and across the country. The recession in our state was less severe than was the recession of the early 1990’s, and less severe than was the recent recession in many states because of the the overall health and strength of our state’s banking institutions. Nevertheless, one fallout from the financial crisis appears to be a growing market share for credit unions in the state. As the chart below shows, since the recent recession, deposits at credit unions have grown much faster than deposits at NH banks overall. Deposits at NH community banks have grown faster than deposits at all NH banks, suggesting that deposit gains by credit unions have come largely at the expense of large banks in the state, as deposit growth for all NH banks is much lower than the growth among just community banks. Prior to the recession and financial crisis, deposits at NH community banks were growing faster than were deposits at credit unions.

It would be unfortunate if community banking institutions that have had strong commitments and links to their local communities and regional economies are tarred by the actions of institutions from afar. Beyond that, a fundamental change in the market shares for financial services could have significant impacts on the regulation of financial services, on government revenues , and on market shares as the tax exempt status of credit unions contributes to their ability to compete and capture market share. The increased concentration of deposits in the banking industry that occurred during much of the 1980’s and 1990’s may now be occurring among credit unions. As the services credit unions offer and their branching look more and more like those of banks, their ownership and regulatory structure may be the only thing that distinguishes them from banks.

State-by-State Economic Outlook for the Next Six Months

October 19, 2012The Philadelphia Region Federal Reserve Bank is producing a leading economic index for each state. The index contains the same economic variables for each state so it is not customized to the specifics of each state’s economy. Some of the index variables are national (similar to my “PolEcon NH Leading Index”) but all of the key economic indicators included yield important information about the likely direction of any state’s economy. The graph below from the Philly Fed suggests that NH, along with VT and CT, will lag the region and much of the country in economic growth over the coming months.

The Philly Fed index isn’t designed to predict just job growth like PolEcon’s (my) NH leading index, but the two indices move in similar ways with changes in the NH economy. I’ve test the ability of both to accurately forecast near-term (6 month) job growth and the PolEcon index does a significantly better job. But the PolEcon Index was modeled and fit specifically to NH data, testing a number of economic variables that have the strongest relationship to NH’s near-term job growth. Doing that for 50 states might be prohibitive, especially for an institution (The Philly Fed.) that primarily serves one economic region of the country. I like the Philly Fed index because and it is great to have a readily available (read free), state-by-state, near-term, economic outlook from a respected and unbiased source. I like it even more when it agrees with the PolEcon Index, as it does now.