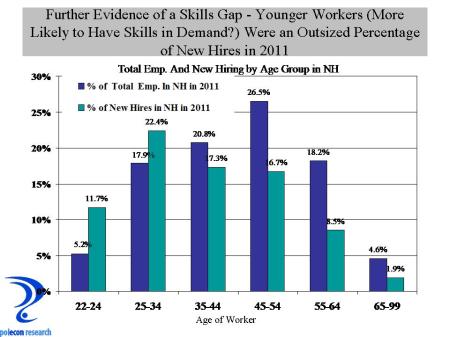

A late boss of mine used to say “We all know the time when education in this country started to go downhill; it was the day after each of us graduated.” I am trying to not let nostalgia influence my views of the current labor market and prospects for job and economic and growth. In prior posts I have tried to make the case that slower labor force growth (and to a degree a skills gap) is the fundamental factor constraining growth in the NH economy. In my last post I wrote: “Looking ahead, population and demographic projections show that both nationally and in NH, the working age population (defined here as age 18-64) will show almost no growth over the next 25 years.” If that was written in another’s blog I would have dismissed it if it was not empirically supported, especially if it was as fundamental to the analysis as it was in my post. Regardless of whether you agree with or have even read the analysis in that post, the population and labor force trends it references are keys to understanding critical obstacles to future economic and employment growth. In this post I provide some documentation and my interpretation of those trends.

It is important to make the distinction between growth in the “working age population” (which my prior post referenced) and “growth in the working age labor force,” (which is a more appropriate measure for the main thesis in that post.). While the two measures move in the same direction, the magnitude of change can differ as the age composition of the population changes and as trends in labor force participation among different age and demographic groups change over time. Longer-term trends (as opposed to shorter-term or cyclical trends – those affected by business and economic cycles) in labor force participation can mitigate or exacerbate some of the population trends affecting the size of the labor force.

“Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future”

—Neils Bohr, Nobel Laureate in Physics

First, let’s look at the assertion from my prior post that: “the working-age population …..will show almost no growth over the next 25 years.” That is a remarkably imprecise statement on which to base any analysis and its accuracy depends on your definition of “almost no growth,” as well as how you define the working-age population. The chart below shows the U.S. Census Bureau’s “middle scenario” for U.S. population growth to the year 2060. In the chart I show four definitions of “working-age population” along with the cumulative growth rate of each. Three of the four definitions begin at age 22 to reflect the adult working age population. The three definitions include: ages 22-64 that recognizes a historical traditional retirement age at 65, as well as two others (ages 22-69 and ages 22-74) that reflect mortality, health, occupational, and retirement trends that have many individuals working beyond traditional retirement ages. To show that adding the younger population has relatively little impact on the trends I include a traditional definition of working-age population that includes individuals ages 16-64.

The chart shows that the “adult working-age population” is projected to grow by about 10 percent over the next 25 years (between 2015 and 2040) in the first two (more traditional) definitions of working-age and by a much larger 15 percent for the definition that extends “working-age” population to ages 22-74. “Almost no growth” may overstate the decline in the rate of growth but, for me, 10 percent growth over 25 years is pretty close to almost no growth, especially by historical standards. I think the chart highlights the important role that older individuals could play in employment growth in the future. I like to call this the “revenge of the baby boomers” who first entered the labor market in competition with large numbers of other boomers and who experienced resulting demand for their labor that could not always keep up with the big increase in supply. Much later in life boomers who wish to continue working will likely see demand for their labor higher than it has been in the past for older workers.

The Distinction Between Population and Labor Force Growth

How growth in the “working-age” population translates into growth in the labor force is a function of the age composition of the labor force and the labor force participation rates among the different age groups in the population. Participation rates are highest between ages 25 and 54, much lower among teenagers, lower among 22-24 olds and much lower and declining at ages 55 and above. Thus when the population is growing in high participation age groupings (between 25 and 54) labor force growth will grow more similarly to population growth than when more of the growth in population is among younger (under 25) and older (55+ individuals). That is illustrated in the following two charts. The chart below compares cumulative population and labor force growth between 2015 and 2060 in the broadest definition of “working-age population” which here includes ages 16-74. Labor force projections incorporate a forecast of an increase in labor force participation rates for all age groups above age 55 (averaging about a 5% increase in participation rates) consistent with projections of participation made by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The increase in labor force participation among individuals aged 65 and above is not simply a result of individuals who are not able to financially retire (although that does play a role), it is also a function of the better health of older individuals and a decrease in the percentage of jobs in the economy that are physically demanding, among other factors. For age groups in the middle age ranges there is a slight decline in participation rates (averaging about 0.4%), and for the youngest age groups a decline averaging 3.6 percent.

Combining the age distribution of the growth in the working-age population with trends in labor force participation shows that actual labor force growth among the population ages 16-74 is going to be much smaller than population growth because so much of the population growth will be among age groups with the lowest labor force participation rates.

When a the “adult working-age population” is examined (including ages 22-69), little difference between the cumulative population and labor force growth is seen, with time periods where growth rates are identical and some during which cumulative population growth is slightly higher.. This occurs because the combination of growth in the ages 55-64 population and an increase in the labor force participation rate of this age group compensates for the decline in participation among the youngest age groups and slower population growth in the high participation age groups (25-54).

Population and Labor Force Growth Over the Next Several Decades Will Support Job Growth That is Less Than One-Half of Current Employment Growth Rates

Each of the graphs above show a labor force that is growing nationally (in fact some states will likely see an outright decline in their labor force). Because the charts show labor force growth it is easy to miss the significance of a slower rate of labor force growth on the U.S. economy and future job growth. Over the past three years the average monthly job growth in the United States has averaged about 200,000 jobs. Real labor force growth hasn’t been sufficient to accommodate that level of growth but because of the layoffs in the labor market during the recession there was enough slack (unemployed individuals and individuals temporarily out of the labor market) in the labor market to allow for that level of job growth. Eventually that slack will be taken-up and job growth will be more constrained because of labor force growth and wages will rise in response to tighter supply (that is just beginning to happen). That was the essence of my thesis about the interaction between NH’s business taxes and demographic and labor market trends.

During the non-recessionary years of the 1990’s the average monthly job growth in the U.S. was about 243,000. Those monthly job growth numbers include jobs going to individuals below the age of 22. While my analysis primarily is concerned with the adult working-age population (ages 22+), including the labor force ages 16-21 into the analysis changes the population and labor force growth trends very little. Even including individuals ages 16-21 into labor force projections labor force growth will not support an increase in 200,000 plus jobs in the coming decades (except following a recession when substantial layoffs and slack in the labor market exist)..

To illustrate that point the chart below translates the annual increase in the nation’s adult labor force into a potential monthly job growth for the nation (if all of the increase in labor force were employed) under four definitions of the labor force. The chart shows that under a traditional (ages 22-64) or a maximum expansion (ages 16-74) definition of the labor force, annual growth will not sustain current or historical rates of monthly employment growth. During years of the highest labor force growth, jobs would grow only at about one-half the current monthly rate of job growth in the U.S.

Caveats and Conclusions

Long range forecast and projections are always problematic but the scenario of slower labor force growth and greater competition for labor outlined in this and my previous post will play out even if the degree to which it does has some uncertainty. Despite the overall U.S. trends it is important to note that population and labor force growth will vary greatly among states. Unfortunately NH and other Northeastern states currently are confronting trends that are on the negative end of the spectrum for population and labor force trends.

When the percentage of women in the labor force increased dramatically beginning in the 1970s the labor market was fundamentally changed and the growth potential of the economy was given a tremendous lift. There are no equivalent transformative changes on the labor market horizon. More individuals will work later into their lives but it won’t have the same economic effects as did the increase in labor force participation among half the nation’s population. In addition there has been on ongoing trend of declining labor force participation rates among young people that is, in large part I believe, attributable to the increase in post secondary school enrollments over the past few decades and this partially offsets increases in participation among older individuals. Perceptions of the need for and value of a at four-year college degree are increasingly being challenged so it is possible that the trend of lower labor force participation rates among the young may begin to reverse. The scenario presented here is based on the assumption that current international immigration and state-to-state migration trends will continue unchanged into the future. It is possible that if labor shortages are severe enough in the northeast, we would we see increased net migration into the region, and once again into NH. But the potential pool of labor which NH can attract will be growing more slowly, making attracting “talent” to the state ever more challenging. That is one reason why I stress the importance of making states and communities attractive to individuals (of all ages) as well as attractive to businesses. Net inter-state migration to NH will likely increase from recent low levels, however, only if the state and its communities offer enough of the amenities and enough of a value proposition to justify that net in-migration. Finally, it is also possible that labor shortages will spur action to increase rates of international immigration to the U.S.. Prediction is indeed very difficult – especially when it is about the future. and especially when it involves a long horizon and as many variables as do population and labor force growth. But for now, my money is on the scenario outlined in this and my previous post.