Linguists will take exception to that and note that a cliff is, in fact, a bluff. The consensus among economists, however, is that the fiscal cliff is indeed no bluff. A number of commentators have noted that the fiscal cliff is more like a slope and will not cause immediate economic calamity. I was one of those as a guest on NHPR’s “The Exchange“. But just as there was once too much hyperbole surrounding the fiscal cliff issue, now, as we get closer to the deadlines when the combination of tax hikes and spending cuts that define the fiscal cliff take effect, there seems to be more of an effort to minimize the likely impacts that will occur if no resolution is found. That would be a mistake because whether the spending cuts take effect immediately or over the course of a year or more, and whether the tax hikes immediately effect spending and investment decisions is not the issue. The issue is that the U.S. economy is simply not growing fast enough to withstand the impacts of the full implementation of the provisions of the fiscal cliff. Skeptics fire away, but below is a succinct chart that shows how the effects of the fiscal cliff relate to real growth in our nation’s economy, assuming the effects of the cliff occur in 2014. To lump all effects in one year isn’t accurate, but the point is to place the magnitude of the cliff’s impacts into context. I believe the context in the chart below highlights the importance of a reasonable resolution to the potential problems the cliff could cause.

Archive for the ‘Fiscal Policy’ category

The Fiscal “Cliff” is No “Bluff”

November 27, 2012How Much Federal Government Revenue is Enough?

November 14, 2012Federal government revenues as a percentage of gross domestic product have averaged about 18% over the past 50 years (the median is also 18%). Federal government revenue is “pro-cyclical,” that means revenues as a percentage of GDP grow when the economy is stronger, as profitability of businesses increases and as individual wage, salary and investment income is increasing. This relationship has a couple of important implications: First, it can confound ideological interpretations of the appropriate level of current revenues as a percentage of the economy because higher revenues as a percentage of GDP aren’t associated with slow growth and low percentages aren’t associated with higher rates of economic growth – just the opposite is true (with the exception of the dual recessions of the early 1980s), second it suggests how important economic growth is to revenue growth and thus to potentially reducing the nation’s budget deficit.

I haven’t done the math but others who have indicate that the various deficit reduction proposals all require revenues as a percentage of GDP of over 18%. The U.S. House passed Ryan budget proposal would produce estimated revenues as a percentage of forecast GDP of approximately 19%, the President’s proposals would produce estimated revenues at 20% of GDP, and the “Simpson-Bowles” model would result in estimated revenues as a percentage of forecast GDP of 21%. That doesn’t sound like much of a difference, but in an economy with a GDP of $15.5 trillion each 1% increase equates to $155 billion in revenue. Going from federal revenues that are 18% of GDP to 21% implies a revenue increase of $465 billion. I could be ok with that if the bulk of the increase were the result of a roaring economy producing large increases in profitability and income, but that isn’t the foundation of any deficit reduction plan and it is hard to see a scenario where $465 of additional revenue is consistent with a high growth economy (the pro-cyclical nature of revenues aside – that relationship isn’t infinitely linear). The national debate over reducing our nation’s budget deficit is framed by two choices or their combinations, increasing tax rates (or eliminating temporary reductions and reducing tax breaks etc.) or by cutting spending. Revenues at 18% of GDP seems to have worked reasonably well over the past one-half century with the past decade being the exception. It may be time to aim for a different ratio for the sake of longer-term fiscal balance, but I wouldn’t do it without first exhausting opportunities for spending reductions that maintain a ratio close to the historical average of 18%. But whatever the combination of spending reductions and revenue increases that eventually becomes the strategy for addressing the nation’s long-term fiscal imbalances, I hope economic growth is the ultimate goal, because as the chart above shows, achieving that goal will make addressing fiscal imbalances a much more manageable task.

Will NH’s Fiscal System Get Better Looking Each Year?

November 9, 2012Up close everyone sees the wrinkles, greys and infirmities that come with age, but some things do, in fact, get better looking with age. Surprisingly, NH’s revenue structure may be one of them. For a lot of people New Hampshire’s fiscal system has been out of balance for a long time. I see it somewhat differently. The state was able to maintain a fiscal structure that was unlike any other in the country. Some hate it, some like, but one thing it absolutely most depends on is balance. Specifically, those identifying with the left of the political spectrum had to be satisfied with doing the things that state government has to do and only a limited amount of what it may want to do. While those on the right of the political spectrum had to be willing to occasionally adjust the tax price of services (adjust rates and fees etc. temporarily or in some cases permanently). Without a recognition of the need for balance from either side, the pressures from one side that were met with complete inelasticity from the other could cause the system to burst. If NH has lost some of that balance I hope it regains it quickly because while some may see our system as flawed, it has also been a big part of our successes.

Looking toward the future, our current system is likely to suffer less from some of the demographically and economically induced changes in the growth in state-level revenues. I don’t know if we will be the envy of other states but we should consider the impacts of the changes before walking too far down the path of big changes. The biggest change is the fact that growth in the working age population is slowing and may continue to do so for decades (see below for NH).

That, of course, implies slower growth in wage and salary income and states most reliant on income taxes will feel that pinch the most. On the flip side, with more older citizens, likely more income will be in the form of interest and dividends, a benefit for NH’s current system if interest and dividends tax revenue grows proportionately . NH’s business enterprise tax (BET) depends on wage and salary payments so that revenue source would be negatively affected but because of the way the BET interacts with the business profits tax(BPT), a decline in either source is cushioned by impacts to the other source. Moreover, as labor becomes more scare, the capital intensity of businesses should increase as businesses look to produce more with fewer people. While the BPT impacts will be mostly neutral, it is possible that a deepening of capital in the economy could increase in the relative profitability of businesses which would provide more lift to the BPT.

As the age structure of the population changes to include more older residents, in the aggregate, less money will be spent on the types of things subject to general sales taxes and more on goods and services that are not taxed (health care being the most notable), thus sales tax revenue growth rates could slow. Combined with more sales occurring digitally via the internet and the generally increasing geographical separation of buyers from the location of sellers, this does not bode well for long-term growth in sales taxes. NH’s hybrid mix of taxes and fees collectively are likely to suffer less as a result of demographically induced changes in revenue . As the risk of impacts is spread over a greater number of sources, any negative impacts on one source will have less of an effect than if the state relied on either of the two major sources of most other state’s revenue, the income and general sales tax. For the most part, property taxes will also be relatively less affected by demographically induced changes.

It may not look like it now, but with the kind of balance that characterized fiscal policy making in NH for decades, and with coming shifts in revenue growth resulting from demographic and economic changes, NH’s fiscal structure may well be better positioned to avoid the next (and inevitable) fiscal calamity to hit states.

Its the Dependency Ratio That Matters Most

November 8, 2012There is a good deal of fretting (warranted) about the impact on national and state-level government spending of a population that is growing older. It is relatively easy to project a path for age-affected expenditures both nationally and in NH and to model how changes in spending programs and policies could alter the projected path of those expenditures. Getting agreement on which policies to alter to influence the spending path is a much more difficult task. What is missing from most discussions is an understanding that aging isn’t the only important demographic trend. The dynamics of an increasing number of older individuals and median age of the population are largely misunderstood, but that is a subject for another post. From a fiscal perspective, the most important indicator of spending pressures resulting from the age structure of the population is the “dependency ratio.” The dependency ratio measures the ratio of working-age individuals in a population to those who are generally more ‘dependent” in a population (that is are likely to draw greater resources from governments then they give to governments). Generally dependency is defined as age groups least likely to be in the labor force (children and those age 65+ – which may be unrealistic as individuals are healthier and for a variety of reasons stay longer in the labor force). The dependency ratio affects both spending and revenues (revenue impacts are mostly missing from the demographic discussion and are the subject of tomorrow’s post). A lot of government spending is directed at these groups – young people via schools and older citizens via things like Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security etc. The chart below shows the rise in the projected dependent population in NH. The chart shows that the past decade has been a “sweet spot” for the dependency ratio in NH, with an overall decline in the percentage of the population in “dependent” years (albeit with an increase in older dependency). I produced a similar chart in the early 2000’s and suggested state government make good use of the state’s time in the “sweet spot” by adopting policies to minimize the impacts of future increase in the dependency ratio in the state (it wasn’t the first nor will it be the last time my thoughts were ignored by lawmakers – in fairness, it’s not always unreasonable for them to do so). Certainly some policies have looked to reduce the impacts of an increasing older population. But with limited, and in some years declines in the youth dependency, less attention has been given to innovative ways to slow the growth in spending (largely education expenditures) in a way that is proportional to growth in the youth population. Effectively managing changes in spending pressures without producing unacceptably large overall increases in spending or unacceptable reductions in services requires that resources not be locked in specific spending categories or programs, but rather be allowed to rise and fall and flow to and from programs programs and services most influenced by demographic and economic pressures. Tomorrow: The other side of the ledger – demographic influences on revenues.

Whoever Wins, I’m Rooting for Propserity

November 6, 2012The winners of today’s state and national elections face some daunting budgeting tasks. Compounding those difficulties is the fact that winners will likely begin their efforts having disappointed close to 50 percent of the people who care enough about their country and state to exercise their right of franchise. Its hard to set a course when half the oarsmen and women are are using them to poke you in the eye rather than right the ship of state. This is not a circumstance unique to this election, but what does seem different is how many people think they still win even when their candidate loses, if the country or the state fail to prosper under the administration of the victor. Some may have, but I never have been better off when the economy is weak, so whether or not my candidates win today, I’m rooting for prosperity.

In NH, today’s winner of the race for governor will confront pent-up demand for limited state resources that show no near-term signs of significant increase. The state’s largest source of general fund revenue, the combined business profits and business enterprise taxes, has shown limited growth recently. In the past, this source of revenue has demonstrated an ability to rise quickly and dramatically as the state’s and nation’s economies rebound, but a severe recession and changes to the state’s business loss carry forward provisions will dampen some of these effects that typically occur early in a recovery. The chart below shows the seasonally adjusted, annualized, business tax revenue over the past decade, along with our forecast for the next two years. This forecast uses a statistical model (ARIMA) that makes no assumptions about changes in the strength of the economy and it indicates that, without significant changes, business tax revenues can be expected to increases by about 5.3 percent over the next two years. We will update the forecast as new data becomes available as well as use modeling that incorporates key assumptions about changes in state and national economic variables, but as it stands now, it appears that little of the pent-up demand for state spending is likely to be satisfied under the current path.

What Will the “Fiscal Cliff” Mean for NH?

October 30, 2012For an economy struggling to gain altitude it is hard to see how the impending spending cuts and tax increases associated with the “fiscal cliff” will do anything in the short-term but bring the economy to stall speed or push it back into recession. At a time when compromise is seen as weakness and ideological impurity, an agreement must be reached in order to avoid the negative effects of the the fiscal cliff. Depending on what is included, the ‘fiscal cliff includes anywhere from $500 to $700 billion in combined spending cuts and tax increases (many via the expiration of temporary cuts).

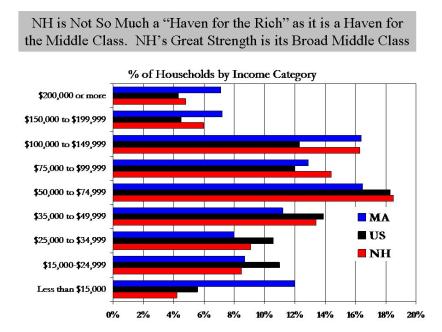

All states will feel the effects of the elimination of the temporary cut in the payroll tax but states with a higher percentage of high-income taxpayers will likely be affected more by the expiration of Bush era tax cuts. Despite often being characterized as a “tax haven” for the rich, NH is much more a “haven for the middle class” as it has a somewhat higher percentage of high-income households than the U.S. (but much lower than MA) and a relatively smaller percentage of lower- income individuals. The percentage of high-wealth individuals in NH is above the U.S. average, but the percentage of income taxes paid by those making $200,000 or more in NH is lower than 24 other states.

States where higher-wealth individuals pay a larger portion of the state’s tax burden are likely to be relatively more affected by the tax cut expiration provisions of the fiscal cliff. But NH will still see an estimated increase in payroll taxes of about $650 million, a significant drop in disposable income in the state. In addition, a study by George Mason University’s Center for Regional Analysis estimates that the defense department and non-defense department budget cuts that will result from the fiscal cliff will cost NH about 6,300 jobs and $325 million in labor income. NH no doubt will take some solace from the fact that Massachusetts is likely to see nearly 10 times the job losses from budget cuts to defense and other purposes (especially medical) and as a result of their high percentage of high-wealth households.

I want to think a reasonable resolution will be found that avoids the worst of the potential problems from the fiscal cliff. Fiscal tightening is clearly warranted, and it appears almost certain that at a minimum the payroll tax holiday will be allowed to expire as well as the Bush era tax cuts for upper income households. It is also almost certain that long term unemployment insurance benefits will be allowed to run out. After that, it all depends on one four-letter word – compromise.