Community banks’ share of the U.S. banking market has declined significantly over the past two decades but since 2010, around the time the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was passed, community banks’ share of all U.S. banking assets has shrunk at a much faster rate. Dodd-Frank may be offering consumers greater protections (data on that issue is not readily available and is less straightforward in any case), but the data clearly show that legislation designed to prevent another “too big to fail” financial crisis is also accelerating the declining market share of community banks, contributing to consolidation in the banking industry, and perhaps helping to create more “too big to fail” institutions. The chart below shows how the volume of assets and loans have changed since the passage of Dodd-Frank for community banks (defined here as those with less than $1 billion in assets), banks with $1 to $10 billion in assets (some researchers consider these banks to be community banks), as well as banks with over $10 billion in assets.

Other than bankers and their regulators, nobody really cares about the market shares of different sized banks, but the out-sized role community banks play in lending to small businesses and the critical role community banks play in smaller communities and rural regions of the country make it an important economic issue for a large slice of the U.S. economy. In almost one-third of the nation’s counties the only depository institutions located in the county are community banks according to a study by the U.S. General Accountability Office (GAO). Small businesses also depend disproportionately on community banks. The chart below shows that despite holding only 14 percent of all loans in the banking industry in 2006, community banks held 42 percent of all small business loans across the country. The chart also shows how the rate of decline in the share of all loans held by community banks, as well as small business loans, have accelerated since 2010.

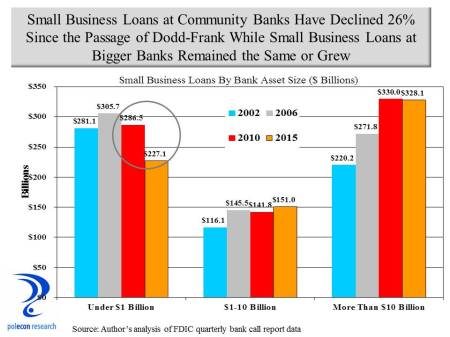

More troubling than the loss of market share by community banks (after all, does it matter as long as lending to small businesses increases?) is the sharp absolute decline in small business lending by community banks since the passage of Dodd-Frank. I think it matters a lot that community banks’ share of lending is declining because of the traditional role of relationship banking and the willingness to consider “soft information” has played in community bank lending decisions and the implications for access to credit by small businesses. As the chart below shows, as recently as 2006, community banks were the largest source of small business lending by the banking industry. Since 2010, however, small business loans at community banks have fallen sharply.

Some of this is the result of consolidation, smaller community banks being acquired by larger, non-community banks. But even that is influenced by Dodd-Frank. Any regulatory requirement is likely to be disproportionately costly for community banks, since the fixed costs associated with compliance must be spread over a smaller base of assets. As the GAO reports, regulators, industry participants, and Federal Reserve studies all find that consolidation is likely driven by regulatory economies of scale – larger banks are better suited to handle heightened regulatory burdens than are smaller banks, causing the average costs of community banks to be higher.

The implications for small businesses and for the economies of smaller and more rural communities are clear. As regulations require more standardized lending and reflect bigger bank processes and practices, community bank lending will be constrained and because they are a major source of small businesses loans and major source of local lending in most rural areas, small business and the economies of smaller, more rural communities will be disadvantaged. Automobile, mortgage, and credit card loans have become increasingly standardized and data driven. These loans are increasingly made without any personal interactions, via the internet and by less regulated institutions, or by larger banking institutions with the infrastructure to make exclusively data driven lending decisions. Business loans are different. Community banks have had to focus to a greater extent on small business and commercial real estate lending – products where community banks’ advantages in forming relationships with local borrowers are still important – as more types of loans have become increasingly standardized. Community banks generally are relationship banks; their competitive advantage is a knowledge and history of their customers and a willingness to be flexible. Community banks leverage interpersonal relationships in lieu of financial statements and data-driven models in making lending decisions, allowing them to better able to serve small businesses. Regulatory initiatives such as Dodd-Frank are more reflective of bigger bank lending processes which are transactional, quantitative and dependent on standardization. Understanding the financials of a business, its prospects, the local community in which it operates, or the prospects for its industry, are hard to standardize. Community banks ability to gather “soft information” allows them to lend to borrowers that might not be able to get loans from larger institutions that lend with more standardized lending criteria. The less “soft information” is incorporated into lending decisions, and the more costly become the regulatory requirements on banks, the more community banks will diminish and with it an important asset for small business, and small communities across the country. It is possible that someday small business lending can be more standardized, less interpersonal, in a way similar to credit card or auto loans and in a way that does not disadvantage small businesses, but I am skeptical.

The debates surrounding financial services regulation since the “great recession” have focused on the safety and soundness of the financial system and on consumer protections, both important objectives, and to be fair, the banking industry too often appears only self-interested in regulatory debates. But far too little consideration has been given to the impact of new financial services regulations on small business, communities, and rural regions of the country.

Authors Note: I have done some studies for the banking industry in the past. This post is not an effort to shill for their interests. This blog is about timely topics that interest me and a place where I can write about them free of any compensated interests. It is an outlet for my analytical interests and opinions. I do confess, however, an affinity for community banks and the people who run them because of the strong commitment that they demonstrate to the people, businesses, and communities in which they operate.